You have probably heard about the impact of stress on memory. Remember those crazy ‘mental blocks’ you would get in high school during a math or English test? How about the famous meme which reads: “The brain is the most complex machine in the whole world. It works 24/7 from birth till death…except during exams.”

Well, it turns out that meme is right! And those mental blocks you had during tests? They were real! The brain truly does ‘stop’ during exams and other stressful situations. It may be able to keep us alive, but it becomes unable to search our memories or store new information.

How does this happen? Is it a mistake? Do we all have a defect that causes us to suffer from these ‘blackouts?’ Let’s find out!

The First Possible Trauma

The first possible trauma a human can suffer from is being abandoned at birth, literally or figuratively. Physical abandonment means the parents have physically removed themselves from the baby’s life. Figurative abandonment is a little more complicated. It might include the parents not giving the baby enough attention or stimuli, or putting it in uncomfortable situations where it doesn’t feel safe or understood. Either way, both types of abandonment put a significant amount of stress on the newborn.

Even before a baby learns to speak, it actively responds to its mother’s non-verbal communication and is sensitive to interactions with the people in its life. When a baby is satisfied with its interpersonal interactions, it feels protected and loved. In mammals, like us, these feelings of bonding and connection are formed and stored in the hippocampus, alongside the rest of our memories.

What is the Hippocampus? How do Genes and Environment Determine Its Function?

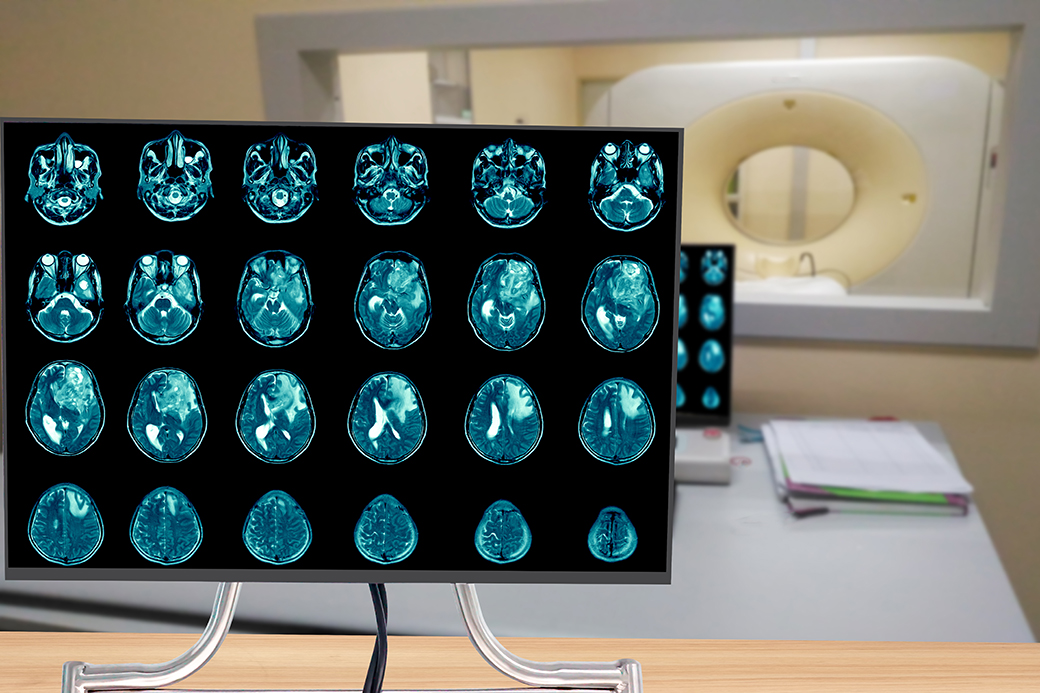

The hippocampus is a region in the brain where operative memory – new and temporary information, like school lessons – is converted into long-term memory. The hippocampus relates this new information to old structures, thus consolidating knowledge.

Laboratory studies have demonstrated that mammals who were physically or figuratively separated from their mothers found it more difficult to overcome adverse situations throughout their lives, including normal stressors.

In addition, these mammals became more biochemically prone to stress due to their expression of genes known to trigger stress. As a result, these mammals are more prone to fear caused by all sorts of stimuli, not just memories of abandonment.

This shows that our parents have not only given us genes that make us more or less susceptible to stress, but also that they have played significant roles in the expression of genes due to the ways in which they treat us during infancy.

Simply having certain DNA is not what affects our abilities. In fact, our environment affects how our DNA is expressed. It might sound crazy because we are often mislead into believing that our genes determine our potential, but Michael Meany demonstrated that there are other factors at play. Similarly, the Reiss group proved the influence that interactions between parents and their children have on gene expression.

During childhood and adolescence, the brain sculpts itself at high speeds, pruning underused neuronal connections like dead limbs on a tree and creating new ones to aid in development. But just because these periods are when most ‘brain remodeling’ takes place doesn’t mean they are the only ones: our brains actually have the ability to learn until we die!

When a new neuron is born, for example a neuron destined to create a memory circuit, it only takes about a month for it to position itself and create thousands of new connections with its neural neighbors. These connections are then reinforced over the next five to six months. Through human repetition – repeating actions, classes, skills, etc. – our brains create new neural connections and allow existing ones to grow stronger. These connections are used by hippocampal cells to retrieve memories. When we are exposed to stress, they stop their migration, hence that ‘mental block’ on your high school exams!

In stressful situations, our bodies create and release a hormone called cortisol into our blood. Cortisol is good in moderate amounts because it allows our bodies to respond to certain stimuli. However, when an excessive amount of cortisol is produced and released into our blood, it can have negative effects on our health and lead to cardiac issues, metabolic diseases, aaaaand… yes! the destruction of hippocampal cells!

High amounts of cortisol also stimulate the amygdala – the part of brains which triggers fear, both inherited and learned. It also impairs the pre-frontal cortex – where our memories are stored. Unsurprisingly, these two issues cause us to be more frightened by stimuli than we might be without high levels of cortisol in our blood.

It’s important to highlight that this process does not affect all kinds of memory because it is only our emotional memory that is enhanced during stressful situations. Cortisol amplifies the amygdala’s ability to remember the context in which we are experiencing ‘danger.’ The result is a ‘learned fear’ that we can respond to more efficiently next time the situation repeats itself.

Why does this occur? Most likely for evolutionary reasons. When we experience stressful situations our bodies use the experience to prepare for potential future dangers. For example, if we see a bear, the HPA axis in our endocrine system secretes cortisol, which triggers a ‘fight or flight’ response. It is a primitive, automatic response, which is important because spending vital time thinking while facing down a bear could lead to a pretty negative outcome. So, the rise in cortisol is the brain’s way of telling the body to survive, not think, thereby shutting down our ability to reason and allowing our primitive reflexes to take the wheel.

As you’ve probably figured out by now, cortisol causes us to focus on our emotions rather than our knowledge. It’s a self-defense mechanism adapted to make us highly responsive in survival situations. Though the functions of the hippocampus are depressed during these stressful situations, the good news is that the neural connections that are destroyed when cortisol enters the blood stream are eventually regenerated once the cortisol disappears.

Everything in the human body is meant to have a precise equilibrium. Some people think of cortisol like it is a villain to defeat but, in reality, we need it to survive. Let’s look at an example: What would happen if you put a 15-year-old into a third-grade class? Well, he probably wouldn’t pay much attention. He’d be bored. There would be absolutely nothing challenging about the course. It would be so easy that he wouldn’t produce enough cortisol to focus his attention on the teacher. Now, put that same teenager in an astrophysics class and he would likely be very stressed because he doesn’t have the tools to keep up with the material. He would be stressed, and that stress would signal his body to produce cortisol, which would allow him to focus his attention.

It is important for our bodies to produce the proper amount of cortisol needed to face specific challenges. Just enough cortisol helps us focus our attention, overcome obstacles, and learn, while too much cortisol triggers our fears.

Abercrombie conducted a study in which participants were injected with different amounts of cortisol and then asked to memorize a list of words and images. The individuals who were given moderate amounts of cortisol wound up being most successful in remembering the words and images. This tells us that being in an adequate environment during learning helps boost our ability to learn, while a stressful environment impairs knowledge acquisition.

Let’s try something. Imagine a man with two children finds himself in a tough financial situation. The basic needs of his children would probably be his top priority, and meeting those needs would be very stressful. All that stress would probably impair his ability to learn a new task.

We can also imagine a teen who is bullied at school and suffers great psychological stress because of it. Because school is a center of social interaction, psychological problems that start on campus often directly impact the way a bullied teen sees the world. It will also likely affect his ability to focus in class.

All of those imaginary situations illustrate how stress leads to deficient memory ability.

As we can see now, any kind of trauma can physically impair our capacity to store long-term memories or inhibit the ability of our brains to compare present and past situations in order to judge if a ‘fear response’ is necessary. Situations like simply being watched or hearing a loud noise can trigger fear because, even if we have experienced such situations before, sometimes we aren’t able to properly evaluate them. Trauma can also enhance the ‘fear response.’ That’s exactly how memory is affected by trauma!

References: